|

|

|

|

67

Interview

Dr. Ernest Small is a Principal Research Scientist at the Eastern Cereal and Oilseed Research Centre, in Ottawa, a section of Agriculture & Agri-Food Canada (AAFC), the Canadian federal government ministry of agriculture. He is the author of seven books and 200 scientific papers dealing with economically important plants, including about two dozen publications on Cannabis. He has testified as an expert botanical witness in dozens of courts cases in North America, and has been a research consultant to governments in the United States and Canada on legislation concerned with plants, particularly Cannabis. Dr. Small has received several professional awards and honors for his scientific achievements. This e-mail interview was conducted in December 1999 by Robert C. Clarke.

What is your academic background? Have you ever taught at a university?

From 1963 to 1966 I obtained three degrees from Carleton University in Ottawa (B.A., B.Sc. (Hons.), M.Sc.), and in 1969 a Ph.D. from the University of California. Since then, I?ve been employed with AAFC. I have occasionally taught university courses, held adjunct professorships, and supervised theses, but most of my career has been spent as a research scientist, with occasional management responsibilities.

How did you come to work with Cannabis?

In 1970, our federal health ministry (Health Canada) became interested in growing a standard supply of medicinal marihuana for pharmacological research, and in clarifying some basic botanical issues about the species for forensic purposes. As well, the Le Dain Parliamentary Commission undertook a very extensive examination of the medical, social, and legal issues concerning Cannabis in Canada. AAFC placed me in charge of the botanical research, as well as the cultivation of the supply of medicinal marihuana. And, I was seconded to assist the Le Dain Commission half-time, by preparing a report on agricultural and botanical aspects of Cannabis.

Who directed that the Agriculture Canada Ottawa Cannabis farm be started and what was your initial mandate?

As noted above, cultivation of Cannabis was initiated by two Canadian federal ministries, Health Canada and AAFC, for the purpose of clarifying a number of botanical issues, and to grow a standard supply of medicinal marihuana. A 3 acre plot was established in 1971 in the main agricultural research area in Ottawa, known as the Central Experimental Farm, where both high-THC and low-THC forms were cultivated. This was in a rather open location, and elaborate security measures proved necessary. After 1971, it was decided to conduct cultivation in Ottawa only in more secure indoor areas, and this lasted until 1979. Outside of Ottawa, hemp has occasionally been grown outdoors at various AAFC stations across Canada in recent years, but currently cultivation is entirely on the private property of cooperating entrepreneurs. I am cooperating in research on hemp, both in the field and greenhouse, but the research sites are not in Ottawa. Our current mandate is to assist the private sector in conducting commercially oriented research on low-THC Cannabis, i.e. industrial hemp.

Did anyone else have a Canadian permit to carry out Cannabis research during this era?

Research cultivation of non-narcotic hemp for commercial development has been carried out under license in Canada only since 1994, and commercial cultivation only since 1998. In the preceding several decades, there was occasional growth of Cannabis under license for various pharmacological and forensic research purposes. Until 1994, virtually all of the authorized cultivation that took place in the last half century in Canada was oriented in some fashion to issues of law enforcement or pharmacological research, and not to the possibility of commercial cultivation in Canada.

Had you been following the international Cannabis research literature and attending conferences?

My first 10 years as a professional scientist were mostly devoted to Cannabis, but after that most of my research was on other crops of more immediate priority to Canada. Nevertheless, one doesn?t loose interest in a plant as amazing as Cannabis, and my literature collection on it has accumulated to occupy several filing cabinets. My return to working on hemp in the last 2 years reflects a widespread perception that hemp represents a promising new crop for Canada. I was a speaker at the international convention of the Hemp Industries Association, held at Hockley Valley, near Toronto this past September, attended the North American Industrial Hemp Council annual meeting in Chicago in November, and hope to attend upcoming major meetings.

How did you obtain seeds for the Ottawa Cannabis farm?

Curiously, it was easier to obtain seeds of Cannabis for research purposes in the early 1970s than it is today, and by 1971 I had accumulated in excess of 400 different stocks of seeds. The United States Department of Agriculture supplied dozens of samples, but today informs inquirers that it has none. Similarly it is also increasingly difficult today to obtain hemp seeds from some other seed banks. In my early research I concentrated on means of distinguishing drug and non-drug strains, and numerous police forces around the world cooperated in supplying seeds from confiscations. Today the emphasis is on non-drug strains, and it is necessary to have a reasonable indication that imported seeds are non-drug. And of course, with the recent realization that hemp is an extremely promising crop for which seed collections are critical for future breeding, many private seed collections are available only on a cooperative developmental basis.

Which accessions matured in the Ottawa climate?

Cannabis is a short-day plant, and both wild hemp and cultivars selected in various regions of the world are rather precisely photoperiodically attuned to flowering and maturing seed according to the latitude of origin. This means that southern European cultivars often mature seeds too late in the season when grown in Canada, which may not be a problem if one simply wishes to harvest fibre, but is a problem where the objective is to harvest the seed. This is a critical issue for Canada since most hemp produced in this country is dual-purpose, i.e. harvested for both fibre and seeds. High-THC forms that originate from southern Asia and Africa also are adapted to much longer growing seasons than found in much of Canada, and usually merely start to mature seeds before being killed by frost in Canada. This is advantageous in at least one respect: pollen from illicit marihuana plantations is less likely to contaminate the seed produced in fields of industrial hemp. Although the suggestion has been made to grow more than one crop in a season, this doesn?t seem practical in the short season of Canada. We have grown extremely early-maturing cultivars, but these matured in midsummer, too early to produce much of a harvest. It would seem preferable to have cultivars that take advantage of the entire photosynthetic season, maturing in the fall. The majority of the more than 60 accessions we grew in our Toronto area plantation this past summer proved to be suitable in maturation time. However, several of the more impressively yielding accessions were too late-maturing, pointing out the need to breed cultivars suited to Canada.

What did you learn from growing so many varieties of industrial hemp and drug Cannabis? What was the impact of your research at the Ottawa farm?

As a result of our botanical and chemical studies, we established a formal botanical classification system for Cannabis, that has been very widely adopted. We recognize only one species - C. sativa L., and as described in my 2-volume book, The Species Problem in Cannabis, Science and Semantics, this was critical to settling a forensic debate over the existence of "legal species" of marihuana. Drug forms were placed in subspecies indica while non-drug forms were placed in subspecies sativa. Within subspecies indica, all domesticated forms were placed in one variety, var. indica, and the wild plants were put in a second variety, kafiristanica; and similarly within subspecies sativa the domesticate was recognized as var. sativa and the wild phase as var. spontanea. Since the cultigens intergrade with each other and with widespread weedy forms, all classifications of C. sativa are necessarily inexact. One element of this classification has proven to have a huge impact - the way we separated the "non-drug" subspecies sativa from the "drug" subspecies indica on the basis of a dividing line of 0.3% THC, dry weight basis, in the leaves and flowering parts of the plant. This level of 0.3% THC is now used in the European Economic Community and Canada as a criterion for authorization of cultivation. Cultivars with less than 0.3% may be legally cultivated under license, whereas those with levels of 0.3% or greater may not. In the U.S., the figure of 0.3% has been suggested as a basis for allowing importation of hemp materials for non-human food use.

What part did the United Nations play in your research?

In the 1970s, the United Nations subsidized some of my publications and travel to international conferences. During this period the UN was instrumental in facilitating contacts among scientists working on drug control aspects, and the backing of this prestigious organization facilitated obtaining seeds and information. Of course, the major objective back then was controlling the drug problem associated with Cannabis, not developing industrial hemp as a crop.

Did you have a relationship with Dr. Carlton Turner?s research group at the University of Mississippi?

Indeed we had cordial relationships with Dr. Turner and the Mississippi group for many years, exchanging information and keeping each other abreast of developments. As you know, after his work on Cannabis Dr. Turner went on to occupy the prestigious position of Domestic Policy Advisor to the president of the US. We used a Mexican strain supplied by Dr. Turner to grow a large supply of standardized medicinal marihuana in Ottawa for Canadian use. Climatic conditions in Mississippi and Canada are of course different - a longer, hotter, drier situation in Mississippi, and this resulted in the plants in Mississippi tending to be taller, with much more leaf fall, leaving the remaining younger leaves with higher THC content on the plants. Nevertheless, morphological and chemical characteristics tended to be comparable between the two locations.

What are your current responsibilities at Agriculture Canada?

In addition to my work on hemp, I?m carrying out research on medicinal crops, vegetables and culinary herbs. I recently published three books on these topics, and am working on several additional books. There is a common theme to all of my current work - assisting the Canadian farmer to find new crops that will serve to reinvigorate agriculture. In this regard, I?m extremely enthusiastic about hemp, which has great potential to become a major crop in North America.

Do you currently work with international agencies or the United Nations? Are you collaborating with other Cannabis researchers?

The Canadian federal government has policies that encourage formal research collaboration agreements between government scientists and the private sector, and my research on Cannabis is mostly concerned with such collaboration. I?m in cooperation with Dave Marcus of Hemphasis Unlimited, a firm located in Toronto. We are assembling a collection of germplasm and evaluating the agronomic importance of our collection for the development of Canadian cultivars. This past summer we grew more than 60 accessions, and will be producing a report in due course. I also have ongoing collaboration with various universities. The paper in this issue of the JIHA, co-authored with Suzanne Montford, is a result of university collaboration. An extensive review of weedy hemp in Canada will shortly be available written with Professor Paul Cavers and his student Tessa Pocock-Whitney, at the University of Western Ontario. I am a plant taxonomist by profession, and great international efforts are underway by taxonomists to create computerized databases with key information on the world?s plant species. Since I have long specialized on the Cannabaceae, I am naturally responsible for this family in several of these international projects.

How did you first learn that Europe was looking into growing industrial hemp? Did you imagine that hemp would ever be grown in Canada?

Like most scientists, I keep abreast of the literature by means of profile searches, so that I have been aware of research trends with respect to hemp over the years. The resurgence of development of hemp in Europe was reflected by an increasing number of research studies, notably in the last 15 years, and especially in the last 5 years. I confess that I did not foresee the day when commercial hemp cultivation in North America would resume.

When was the 0.3% THC threshold for industrial hemp first suggested and from where was it derived? Did this standard replace a previous one?

Over the years, different researchers have suggested different levels of THC as means of recognizing groupings within Cannabis. It has long been appreciated that "drug" selections of Cannabis, with high levels of THC, originated from southern areas of Eurasia and from Africa; and in contrast selections of Cannabis used as sources of fibre and oilseed originated from northern Eurasia and had very limited drug potential. As documented in my publications in the 1970s, we picked the level of 0.3% as a formal means of separating the two classes of plants on the basis of numerical taxonomic methods. We grew several hundred different accessions, recognized the two groups on a number of physical and physiological characteristics independent of THC level, and the 0.3% THC level was calculated to be the concentration that naturally best separated the two groups. As a specialist in plant classification, it has been extremely gratifying to have so much of the world apply our simple classification in a practical way. But I would caution that 100% separation of groupings within species is rarely achievable, and this is the case for Cannabis sativa. Because of seasonal and diurnal fluctuations in THC content, a given plant could have more or less THC than 0.3% at different times. There are also minor environmental influences on THC content, and variations and errors in sampling method will also influence reported THC levels. In Canada common sense has been exercised by the authorities when levels slightly exceeding 0.3% have been found (by law, hemp fields must be eradicated if the level is higher than 0.3%). It should also be appreciated that the level of 0.3% is well under the concentration of 0.9% THC considered minimal for psychotropic effects by some authorities.

When did the Canadian government first investigate the feasibility of industrial hemp? Did you know about the promise of industrial hemp farming in Canada before 1994 when Joe Strobel and Geoff Kime grew the first Canadian crop? Were you called in to assess the Hempline application to grow hemp?

I have advised the Parliament of Canada, Health Canada, and our Justice Department for many years on legislation and research applications concerning drug plants, particularly Cannabis, and so am familiar with how hemp came to regain respectability in Canada. Until the Strobel and Kime application in 1993, the idea of reintroducing hemp as a Canadian crop was not taken seriously, and indeed in common with the US, our authorities considered this unwise in view of the problems posed by narcotic forms of Cannabis. Key to the change in climate was educating the Canadian authorities that the word "hemp" or the phrase "industrial hemp" should be reserved for the non-drug class of Cannabis, and was different from the drug class that produces marihuana. By the early 1990s, it was becoming obvious that the hemp industry was developing in a responsible way in Europe. Canadian farmers and entrepreneurs saw the possibility that hemp could be grown in Canada just as in Europe, with appropriate safeguards. With increasing demand by the private sector, and with support from key members of the federal government, as well as several provincial governments, the climate had changed sufficiently to enact regulations permitting the development of a commercial hemp industry.

Did you advise on the varieties to be approved for planting in Canada and suggest stipulations for harvest?

A committee was established to advise Health Canada on such specific matters. While I gave advice to members of the committee, I did not directly participate in the specific regulations that were enacted. I myself am subject to the regulations that govern research on hemp in Canada. I expect that with experience, some of the constraints will be eliminated from the regulations.

What are the characteristics of wild plants that may prove of value in breeding projects? Do you have plans to collect feral/wild seed and to breed with them to make new varieties?

Wild plant germplasm is essential to the improvement of crops, and hemp is no exception. Feral hemp in North America, popularly known as "ditchweed" in the US, is derived mostly from low-THC fiber cultivars grown before authorized cultivation ceased in 1945. These plants are of particular value to North Americans because natural selection has adapted them to local conditions of climate, photoperiod, soil, disease, and herbivory. Despite widespread efforts at eradication, populations still persist in North America, and deserve to be maintained for crop development. Indeed, we have initiated a program to collect and maintain wild North American hemp seed, and the possibility is being considered to use these for breeding purposes. Old World wild hemp populations have existed for millennia, exhibit a wider range of physiological and morphological features than North American ruderal plants, and so also are of considerable significance as germplasm. For the most part, structural features of wild plants are much less desirable than the genes for physiological resistance that wild plants contain. Small seeds with thick achenes, as are characteristic of wild hemp seeds, are not desirable for oilseed cultivars, although it is probable that wild plants do have genes that can improve the already impressive nutritive profile of the oil. Irregular branching, short internodes, and considerable wood in the stems, as are characteristic of wild plants, are not desirable for fibre cultivars. Possibly, wild plants could be used directly for some purposes. The exceptional branching and floral production of some wild plants can contribute to the production of essential oils, although this is currently of minor commercial significance. The relative ability of wild plants to withstand no-till or low-till conditions, and the appreciable biomass productivity of some populations, suggests biomass production possibilities, although these may be limited. In large areas of North America, particularly wetlands supporting wild bird populations, so-called "ecovars" (selections from wild populations) of various species are being used for revegetation purposes, and hemp may well be ideal in some situations.

Do you know of any archeological record of pre-Columbian hemp in Canada or elsewhere in the New World?

This is a sensitive topic, since some Native Americans have contended that they have utilized Cannabis sativa as a source of "hemp fibre" since pre-Columbian days, and therefore should be exempted from current laws. Certainly almost all authorities subscribe to the belief that hemp is a native of Eurasia, not elsewhere. Curiously, the same was said about the hop plant (Humulus lupulus, the source of flavoring for beer), the nearest relative of Cannabis sativa. Until a few decades ago, it was believed that all wild hop plants growing in North America were simply escapes from cultivated hops imported to North America from Europe. However, fossil pollen has definitively shown that the hop plant was present in North America before mankind, and moreover my own research has shown that there are three distinctive varieties of the hop plant that occur only in North America. No one has shown the presence of pre-Columbian pollen of Cannabis sativa in North America, suggesting strongly that this species was introduced to the New World. The belief that Cannabis sativa was present in pre-Columbian North America likely originates from confusion over the ambiguous name "Indian hemp". The name Indian hemp has been loosely applied to the drug class of Cannabis sativa (i.e. subsp. indica), an allusion to the historical narcotic use in India. However, the name Indian hemp is also employed for the North American Apocynum cannabinum, which was used by native North Americans as a textile fibre plant. While all this is suggestive that Apocynum, not Cannabis, is the correct identification of ancient North American woven materials identified as "hemp" the situation has not yet been entirely clarified. There is currently considerable debate over the possibility of pre-Columbian voyages having resulted in intercontinental exchange of crops, and it is conceivable that Cannabis sativa (even if it is indigenous only to Eurasia) was transported to the New World well before Columbus, and indeed was adopted by native North American Indians. To settle the question, the fibre in authentic pre-Columbian North American "hemp" garments should be identified.

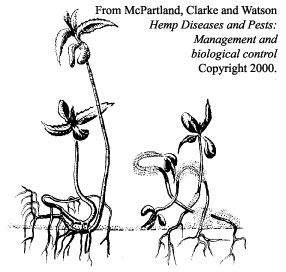

So far, Canadian hemp crops have suffered little from pest damage. Do you expect industrial hemp crops to have pest problems in the future?

Hemp has a reputation for resistance to biological attack, although it has been documented that, like virtually all other plant species, it is subject to a wide diversity of insects and diseases. Nevertheless, most disease and pest problems tend not to be severe. Problems are likely to become more apparent in Canada as acreage increases, so that there will be a need to monitor closely and perhaps initiate breeding to combat harmful species that become especially significant. Organically grown hempseed is particularly desirable for market reasons in North America, and therefore it is especially important to develop the industry to minimize use of biocides.

Where will hemp be in twenty years as a industrial crop? Will Canada have an extensive hemp infrastructure in place?

Most new crops achieve only limited or no success. However, hemp may be different. It really is an old crop, that has been excluded from North America only partly because of the natural operation of market conditions; the bad reputation of drug forms of the species obviously has been a roadblock to success. New and exciting applications have been demonstrated in Europe, and at least the European level of success can be achieved in North America, although it is not likely that the European level of crop subsidies will be provided. There is a genuine excitement and enthusiasm on the part of Canadian and indeed American entrepreneurs that I have not seen matched for any other agricultural plant. Research is a key to future success, and it will be essential to increase productivity, both by development of superior cultivars, and by processing technology. I do believe that Canada will have a well developed hemp industry in the next decades. There are, however, two key issues that will determine the extent of this industry. First is the issue of how much THC is permitted in grain (i.e. seed) preparations intended for human food use, a critical issue since salad oils with healthy profiles have huge profit potential. Currently in Canada, food derivatives of the seeds such as oil and seed cake may contain no more than 10 micrograms/gram of THC (i.e., 0.001%), which is attainable. However, governmental authorities in North America have expressed concern that even this very low level poses health risks, and therefore a much lower level is required. This is not practical, at least with current technology and cultivars. The issue is currently being explored, and represents a considerable threat to the industry in North America. Second, there is the issue of the future of hemp in the United States. The US is Canada?s largest market for hemp products. Should hemp cultivation be authorized in the US, as has occurred in Canada, then competition will be severe from American farmers and processors. On the other hand, should Americans be permitted to cultivate hemp, the considerable tension that now exists over Canadian exports of hemp to the US would be eliminated. I would predict that the longer growing season of the US would favor cultivation for fiber purposes, but that Canada would be very competitive in oilseed production, as is the case for rapeseed (Canola) and soybean.