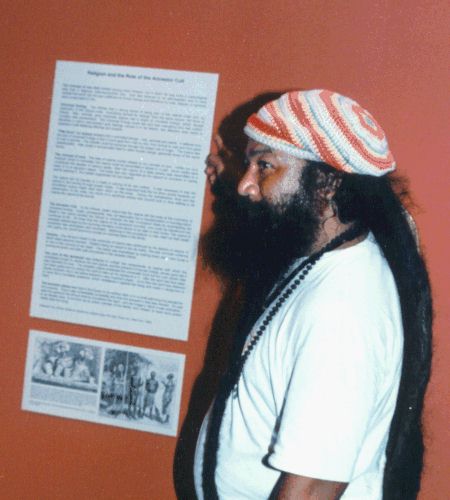

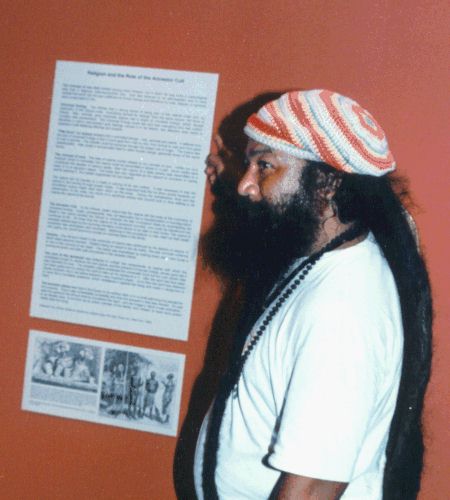

Benny T. Guerrero (Ras Iyah Ben Makahna 1997)

From: Ras Iyah Ben Makahna [makahna@ite.net]

Sent: Monday, August 09, 1999 8:37 PM

To: carl-olsen@home.com

Subject: E-mail version of decision!

IN THE SUPERIOR COURT OF GUAM

| PEOPLE OF GUAM, Plaintiff vs. BENNY TOVES GUERRERO, Defendant. _________________________________________ |

)

CRIMINAL CASE NO. 0001-91 ) ) ) DECISION AND ORDER ) ) ) ) ) ) |

INTRODUCTION

This matter came before the HONERABLE MICHAEL J. BORDALLO on the 20th day of May, 1999 on Defendants, Benny T. Guerrero, Motion To Dismiss and Motion for the Appointment of an Expert on the religion of the Rastafarian. The Defendant was represented by D. Paul Vernier. Assistant Attorney General Gerad Egan represented the Plaintiff, the People of Guam ("the Government"). Because the Court grants Defendants Motion to Dismiss, it will not address the Motion for the Appointment of an Expert.

BACKGROUND

On or about January 2, 1991, the Defendant, Benny Toves Guerrero was returning to Guam from Los Angeles via Honolulu. At the airport, Guam Customs Officers approached the Defendant and asked him if he was carrying any drugs. The Defendant, a practicing Rastafarian, replied that he was not in possession of any drugs. Thereafter, the Customs Officer searched the Defendants backpack and found marijuana contained therein. The Defendant was placed under arrest and charged with importation of an illegal substance. He was subsequently indicted on January 11, 1991 under the charge of Importation of a Controlled Substance (As a First Degree Felony.

DISCUSSION

The Defendant

now request this Court to dismiss the case because of a violation of his First

Amendment free exercise rights. The Defendant was charged pursuant to

statute 9 G.C.A. Section 67.89, which states: Except for a person

registered pursuant to Section 67.95 of this Code or exempted pursuant to

Section Section 67.93 or 67.94 of this Code, it shall be unlawful and punishable

as a felony of the first degree to import into Guam any controlled substance

listed in Schedule I or II as per Section 67.22 through Section 67.25 of this

Code or any narcotic drug listed in Schedule III, IV, or V as per Section

Section 67.26 through 67.31 of this Code.

The Defendant

argues that this statute is inorganic, unconstitutional and inherently violates

his First Amendment free exercise rights. Defendant proclaims himself a

priest of the Rastafarian religion which has its origin in Jamaica. As

part of the rituals and traditions of this particular religion, Defendant

contends that the use of marijuana is a necessary sacrament in the practice of

Rastafarianism. Rastafarians, according to the Defendant, consider the

smoking of marijuana a sacred practice and disfavor it use in a recreational

manner. It is the Defendants position that by criminalizing his use of

marijuana, he is being denied the right to practice his religion,

Rastafarian. Specifically, the Defendant argues that the Organic Act

guarantees an Individual his right to freedom of religion. Under Section

1421b of the Bill of Rights, Guam provides the following protection for the

exercise of religion:

(a) No law shall be enacted in Guam respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof, or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press, or of the right of the people peaceably to assemble and to petition the government for a redress of their grievances. (Emphasis added.)...

(n) No discrimination shall be made in Guam against any person on account of race, language, or religion, nor shall the equal protection of the law be denied.

The 1899 Treaty of Peace enacted when the U.S. acquired Guam from Spain after the Spanish-American War, guarantees the free religious expression of the "native inhabitants of the territories" in two articles:

Article IX. "The civil rights and political status of the native inhabitants of the Territories hereby ceded to the United States shall be determined by Congress.

Article X. "The inhabitants of the territories over which Spain relinquishes or cedes her sovereignty shall be secured in the free exercise of their religion."

The Defendant also directs this Court to consider the 1993 Religious Freedom Restoration Act, ("the RFRA"), adopted by Congress. 42 U.S.C.A. Section 2000bb. The Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993 signed into law by President Clinton in 1993, protects the free exercise of religion. It states:

the government shall not substantially burden a persons exercise of religion even if the burden results from the rule of general applicability person whose religious exercise has been substantially burdened in violation of this section may assert that violation as a claim or defense in a judicial proceeding.

Under the Act,

Congress required government to accommodate religious belief by giving religions

special treatment unless there was compelling reason not to do so. The

Defendant claims that under such an heightened standard of review, the People

cannot adequately demonstrate a compelling reason that justifies it making the

use of marijuana illegal for the Defendant to use within the practice of his

religion. The People, however, argue that the law is one of general

application, and that the Defendant is being charged with importation of

marijuana as opposed to possession. The People, relying on Employment

Division, Dept. of Human Resources of Oregon v. Smith, assert that because the

statute is one of general application, strict scrutiny does not apply, 496 U.S.

913, 110 S.Ct. 2605 (1990) (virtually eliminate the requirement that the

government justify burdens on religious exercise imposed by laws neutral toward

religion.)

The question

then becomes whether the RFRA, which codified the "compelling

interest" standard of the First Amendment, is still viable in Guam.

It is has been established in other context, such as in the Insular Cases, that

constitutional provisions that apply to the States do not apply to Guam, as an

unincorporated territory. See Balzac v. Puerto Rico, 258 U.S. 298, 42 S.Ct.

343 (1922) (Sixth Amendment inapplicable to territories); Ocampo v. United

States, 234 U.S. 91, 34 S.Ct. 712 (1914) (Fifth Amendment grand jury provision

inapplicable to territories). More recently, the Ninth Circuit held that

the Commerce clause does not apply to Guam because Guam is not a State, Sakamoto

v. Duty Free Shoppers, 764 F.2d 1285 (9th Cir. 1985) (The central concern of the

Commerce Clause was that states did not employ discriminatory practices that

favored in-state interests to the detriment of the out-of-state interest.)

The court found that while previous courts had assumed that the commerce clause

applied, the issue was never previously raised or discussed, and hence, it found

that contrary to that assumption, the commerce clause in fact did not apply to

Guam.

The free

exercise of religion is substantially burdened by statute if it requires a

person to refrain from engaging in a practice important to his or her religion,

or forces the person to choose between following a particular religious practice

or accepting the statutes benefit. Hobbie v. Unemployment Appeals Comm'n,

480 U.S. 146, 140-41, 107 S.Ct. 1046 (1987). The Court is mindful of the

Supreme Courts view that the court has no authority to determine the

truthfulness or reasonableness of the defendants convictions. United

States v. Ballard, 322 U.S. 78, 86-87, 64 S.Ct. 882 (1944) (reversible error to

submit the question of validity of religious belief to the trier of fact.);

Hernandez v. Commissioner, 490 U.S. 680, 699, 109 S.Ct. 2136 (1989) (rejecting

free exercise challenge to payment of income taxes allegedly to make religious

activities more difficult.) Notwithstanding, although the courts should

not pass judgement on which religion is bona fide or fake, the Court must make a

preliminary inquiry in order to distinguish sham claims from sincere ones.

People v. Woody, 394 P.2d 813 (Ca. 1964).

The Court

finds that for the purpose of this matter, Defendant has demonstrated that he is

a legitimate member of the Rastafarian religion and has established that the use

of marijuana is a necessary sacrament in the practice of his Rastafarian

religion. See People v. Woody, 61 Cal.2d 716, 394 P.2d 813 (Ca. 1964)

(religious belief may be proven through circumstantial evidence); U.S. v.

Meyers, 906 F.Supp 1494 (D. Wyo. 1994) (minimum threshold to prove religious

belief). The people have not offered anything in opposition to Defendant's

claim, and have chosen to concede the allegations. Thus, this Court will

accept the Defendant's statement on religious beliefs as true, and in the

determination of this matter will not review the validity of those religious

beliefs.

After careful

review of the arguments, this Court finds that 9 G.C.A. Section 67.89 is

inorganic, as applied to this case, violating the Organic Act of Guam and the

RFRA. The Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993, although declared

unconstitutional in state and local jurisdictions, is still applicable to Guam

because Guam is considered a federal instrumentality of the United States.

The Supreme

Court in invalidating the RFRA in state jurisdictions, made no specific

reference to the constitutionality of the act in federal jurisdictions.

City of Boerne v. Flores, 521 U.S. 507, 117 S.Ct. 2157 (1997). Arguably,

Federal jurisdiction are still subject to the application of the act because

RFRA was invalidated under violation of the 14th Amendment Section 5 of the

Constitution. The Supreme Court held that Congress went beyond the scope

of their power by impeding upon the state police power when it required that

RFRA be applied at every level of government.

Because

Congress continues to exercise plenary power over the territories and does not

share that same balance of power with the states, the RFRA is still applicable

to Guam. Under Article 1 Section 8 cl. 17 and Article IV Section 3 cl. 2

of the Constitution, Guam and other U.S. territories are subject to Congresss

plenary power. Because ultimately, the federal government possesses full

and complete legislative authority over Guam, Guam is thus considered a federal

instrumentality. Furthermore, the act itself does not specifically state

Guam is to be considered a state in reference to the application of the

act. The RFRA, although declared unconstitutional in state jurisdictions,

has been endorsed and held up in certain federal courts. Abordo v. Hawaii

902 F.Supp. 1220 (1995); Wisconsin v. Yoder 196 .2d 238 (1995); In Re Hodges 220

B.R. 386 (1998), United States v. Martinez 84 F.3d 1549 (1996).

The Organic

Act also maintains that no statute shall be imposed on the People of Guam that

infringes upon their free exercise right to practice religion. The act

enables us to interpret our own local laws. Therefore, upon finding

Congress intended to resurrect the compelling interest standard, and that Guam

is a federal instrumentality for the purposes of RFRA, it is this Courts finding

that under either the Organic Act of Guam or the RFRA, a law of general

applicability that substantially burdens a persons ability to practice his

religion, must demonstrate a compelling state interest to do so, and that the

statute is the least restrictive means of accomplishing that purpose. The

Court, consequently, must apply the two-fold analysis.

In this case,

the statute prohibiting the importation of marijuana, does not pass the strict

scrutiny analysis because the Government has not demonstrated a compelling state

interest to deny Defendants right to the free exercise of his religion by using

marijuana as a sacrament. The Government has not even alleged that the law

address a compelling state interest. Only paramount governmental interests

suffice to permit limitation upon the free exercise rights. Sherbert v.

Verner, 374 U.S. 398, 83 S.Ct. 1790 (1963), Wisconsin v. Yoder, 406 U.S. 205, 92

S.Ct. 1526 (1972). The Supreme Court has found compelling governmental

interest in maintaining the tax system, Hernandez v. C.I.R., 490 U.S. 680, 109

S.Ct. 2136 (1989); preserving national security, Gillette v. United States, 401

U.S. 437, 91 S.Ct. 828 (1971); ensuring public safety, Prince v. Massachusetts,

321 U.S. 158, 64 S.Ct. 438 (1944); providing public education, Wisconsin v.

Yoder, supra; and enforcing participation in the social security system, United

States v. Lee, 455 U.S. 252, 102 S.Ct. 1051 (1982). Moreover, the law may

infringe on a persons right only if it does so in the least restrictive way

possible. The Government has not alleged or attempted to show the statute

is the least restrictive means of carrying out its purpose.

The People

assert the statute in question is one of general applicability and therefore may

substantially burden the Defendants ability to practice his religion. This

Court has found that the People must put forth a compelling interest prior to

erecting such a burden, and finds that the People have failed to present

one. Therefore this Court finds that, as applied in this case, the Guam

statute violates the Organic Act and the RFRA.

CONCLUSION

Based on the foregoing, the Court finds that, as applied to the specific facts of this case, 9 G.C.A. Section 67.89 violates the Organic Act of Guam and the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993. Therefore, the Court grants the Defendants Motion to Dismiss.

SO ORDERED this 29 Day of July, 1999.

Michael J. Bordallo

Judge, Superior Court of Guam

Benny T. Guerrero (Ras Iyah Ben Makahna

1997)